Even JoJo's Bizarre Adventure's Creator Knew the Anime's Next Part Would Be the Best Yet

In a certain corner of the anime sphere, JoJo's Bizarre Adventure's impending next anime is the talk of the town. With the long-awaited Steel Ball Run all but confirmed, fans are now just waiting for the JOJODAY event on April 12, 2025 to make it official.

Although some are less than impressed by the premise of the horse race, they're surrounded by fans who will swear up and down that Steel Ball Run will be JoJo's best anime yet. That isn't just restricted to fans of the anime, though. Araki himself gave a laundry-list of reasons fans can expect this part to be the anime's best so far, years ago, right at the outset of the part's first manga volume.

Araki Dishes on Steel Ball Run in a Forgotten Afterword

JoJo Creator Breaks the Part's Seismic Changes to the Franchise Down

In the first volume of the paperback edition of Steel Ball Run back in 2017, Araki provided a thought-provoking afterword. In it, he intends to break down his memories in developing Steel Ball Run. It's particularly interesting because hindsight is obviously at work, with the afterword coming 6 years after the end of Steel Ball Run back in 2011. He details five key clusters of memories, labeled as "the protagonists", "stands", "research", "the villain", and "scope".

There are some fascinating tidbits buried in Araki's memory dump. Another interesting fact is that Araki chose to reveal the big enemy of Part 7 right at the outset in Steel Ball Run's first volume's afterword, apparently not considering it a spoiler (advice this article will follow). As it turns out, Araki had inadvertently described the complexity, beauty, and freshness that Steel Ball Run exhibits, and he made the perfect argument for why fans should be antsy for its anime.

Steel Ball Run's Big New Mechanic Allowed Araki to Return to the Start

The Spin Was Fundamentally Based on Something Araki Noticed While Drawing

The ending of JoJo's sixth part, Stone Ocean, was big, all-consuming, and gorgeously grotesque. It probably doesn't need to be explained that the part ends with a universe reset for JoJo. This decision was bound in a lot of anxiety for Araki, who felt that he'd reached the pinnacle of what he was able to do and depict in JoJo's story at that point. However, out of that anxiety came a revelation:

My previous work, Part 6: Stone Ocean, left me with a sense of satisfaction, or perhaps the sense that I had drawn all there was to draw...? I felt a small sense of accomplishment. So what do I do now?

At the time, there was something in my drawings that I was very interested in, and that was rotation (or, to use the proper term, spiral rotation). When I draw flames, I draw them in a twisting motion, like the twist of a splash of water. The twist of the bending joints of a human body. The twist of a growing lock of hair. I draw the branches of plants and trees twisting as they connect to the trunk. I draw petals as if they were whirlpools. I add shading to rocks and stones as if they were rotating, and so on.

Drawing in such a way led me to believe that all the phenomena in the world could be explained by rotation and spirals. If this were a Stand ability, it might just be the most powerful of all. And if rotation is rebirth, then perhaps the story can return to its origin.

Because of Araki's fascination with spiral rotation, he found an idea to start the franchise over from scratch, right at the "same period as part 1: the dawn of modern civilization." Thus was born the Spin, Steel Ball Run's counterpart to Hamon. Araki also opens up a compelling link between part 6 and part 7 here: gravity and time are the obvious reasons behind Made in Heaven's functioning, but the role of rotation is often undervalued—and it feeds directly into the rebirth as the Spin in the proceeding part.

What does this mean for JoJo's anime? Even the imagery that Araki uses evokes it. Steel Ball Run is a part perpetually in motion which will only be propelled by an anime, and Araki's embrace of rotation as an artistic fundamental becomes really obvious when one looks back. From the spiral center of a horse's gallop to the subtle rotation of a fire's flames, Steel Ball Run was built from the ground up to be hypnotically dazzling when it's animated. With the stakes and expectations for anime production growing ever higher, too, the intoxicating style of Araki's singularly philosophical art is sure to be brought out.

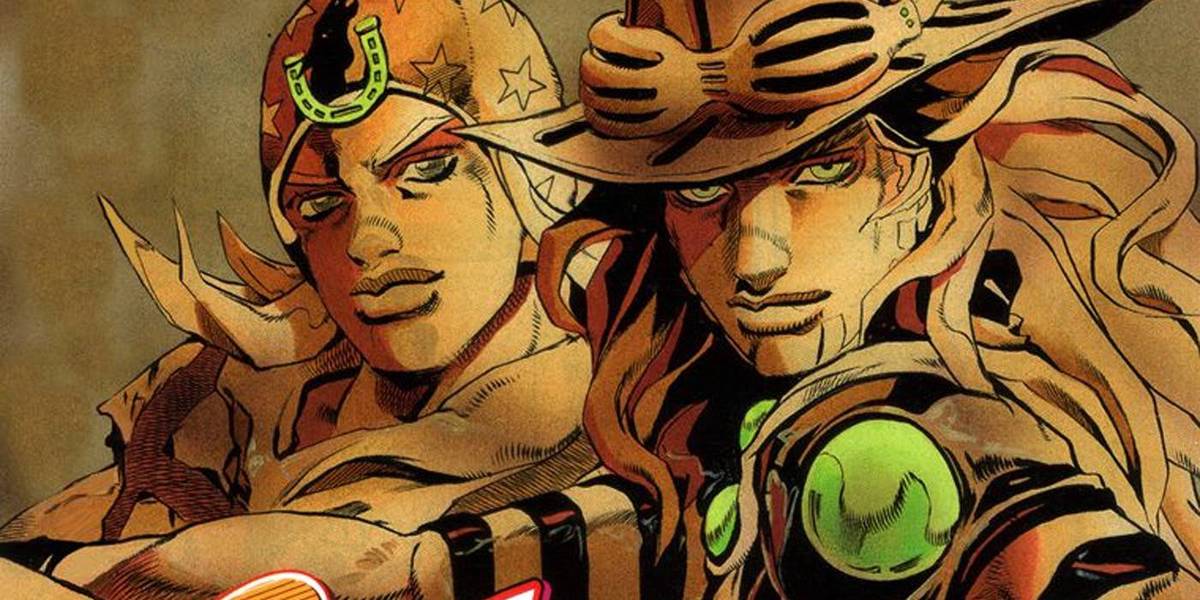

Steel Ball Run Gives Its Characters More Room for Complexity

From Its Main Villain to Its Deuteragonists, Araki Gave Steel Ball Run the Series' Most Compelling Characters Yet

The growth as a storyteller evident in Araki's integration of artistic fundamentals with his narrative is also apparent in how he describes the deuteragonists of Steel Ball Run, as well as the ultimate villain in Funny Valentine. But a crucial context for that is evident in a detail Araki mentions, more so because of its impact on his art: the change from a weekly shōnen magazine, Weekly Shōnen Jump, to a monthly seinen magazine, Super Jump.

For Araki, this allows him to isolate and emphasize the most important scenes, as well as take advantage of the larger page count to depict the isolation and loneliness of the American West. This is the factor that Araki indicates as "scope". But strangely enough, Araki doesn't mention the impact this has on his narrative—it's much more implicit.

The change from a shōnen to seinen magazine also allowed for a great deal more complexity. After all, Araki's trust in his readers to "fill in" details, which his growing emphasis on whitespace and grand landscapes allowed him to leave out, doesn't just have to do with the page count: it has to do with the older demographic, too. Older readers are able to handle more complex characterizations, and this shows through perfectly in Araki's description of Funny Valentine.

JoJo's villains who have been animated so far have been straightforwardly "evil". The only one with moral complexity, really, is Stone Ocean's Enrico Pucci—and even he has the complexity-annihilating fallback of being "manipulated by DIO". Araki instead gives such a solid description of Funny Valentine's ambiguity that readers should see it for themselves:

I'd like to point out that this character is primarily a villain from the perspectives of the protagonists, Johnny and Gyro. President Valentine uses the transcontinental Steel Ball Run race to find a treasure that will make his country the greatest in the world. In other words, he intends to win the people's trust and support through sports. President Valentine knows that the future is moving away from the age of the horse and into the age of the machine. He is also keenly aware that democracy is equal to capitalist economic self-empowerment. Moreover, his selfless motives make him both powerful and utterly terrifying as a character.

In other words, our protagonists—Johnny, Gyro, Mr. Steel, and their allies—are outclassed in the justice of their perspective by President Valentine. And yet, in Steel Ball Run, the president attempting to lead society on the right path is the ultimate evil. Within President Valentine exists a contradiction between justice and evil. He is a paradox. What exactly is happiness, then? If happiness is true victory, will the coming era bring victory? Did Johnny and Gyro win after all?

Indeed, Funny Valentine is only truly a villain for Johnny, Gyro, Mr. Steel, and those who find themselves on their side. His interests aren't just understandable or morally ambiguous; they fall in line, however detestably, with his role as the President of the United States. He never wavers in his sincere devotion to that duty, either. In a landscape where people jump to call anime or their characters "morally ambiguous", Funny Valentine is going to be JoJo's most interesting villain to hit the screen ever.

This extends to Johnny and Gyro as well. Araki doesn't go into excruciating detail, but he does explain his interest in contradiction—much like he explained the contradiction inherent to Funny Valentine's character. It's always been obvious that JoJo is a story about contradictions at its heart, and this bleeds through to its very core thematic aim of being "an ode to humanity". For Johnny and Gyro, though, they receive the benefit of being under Araki's pen right as his narrative interest in contradiction comes into full focus.

It's because of everything else here that Johnny and Gyro are able to shine: the complexity of their growth and values in contrast with figures like Funny Valentine; the way Spin as a mechanic integrates perfectly to reflect their growth as Stand users and combatants; the way Araki's shift to a monthly seinen magazine gave them the literal (and metaphorical) space to breathe as characters. Araki never said it explicitly, but back in Steel Ball Run's first volume, he made it clear why this will beJoJo's Bizarre Adventure's best anime ever.

Source: jojowiki.com for the translated interview.

- Created by

- Hirohiko Araki

- TV Show(s)

- JoJo Bizarre Adventure

- Video Game(s)

- JoJo's Bizarre Adventure, JoJo's Bizarre Adventure: All Star Battle R

- Character(s)

- Will A. Zeppeli, Jonathan Joestar, Giorno Giovanna, Jotaro Kujo, Joseph Joestar, Jolyne Cujoh, Johnny Joestar, Josuke Higashikata, Gyro Zeppeli

JoJo's Bizarre Adventure is a Japanese multimedia franchise created by Hirohiko Araki. It follows the adventures of the Joestar family, spanning generations, each with unique abilities and battling supernatural enemies. Known for its eccentric characters, distinctive art style, and creative battles, it includes manga, anime, games, and merchandise.