Blind Faith: Leaving the White Cane Behind

Blind Faith: Leaving the White Cane Behind

With the help of a dog named Orient and a lot of determination, Bill Irwin became the first blind person to complete the Appalachian Trail.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Hiking a long trail is an impressive feat for anyone. But what if you can’t see, and your guide has four paws? In 1990, Bill Irwin became the first blind hiker to complete the Appalachian Trail. This hike inspired Trevor Thomas (the second blind hiker to complete the AT, in 2009) and many others to hit the trails. In this feature that appeared in a 1991 issue of our magazine, Irwin explains exactly what that inaugural hike entailed. — Emma Veidt, associate editor

WHEN YOUR AVERAGE middle-aged, long-distance hiker completes the Appalachian Trail, he’s lucky if a family member makes the drive to Maine to drive him home. Maybe the hometown newspaper does a small story, and maybe a few friends at least appear interested in the slide show. He dreams of recognition, but it never happens.

Then there’s Bill Irwin. During the final steps of his 2,100-mile journey, over 100 people, including press from around the country, hiked with him and sang “Amazing Grace.” When he finally stepped off the trail, he was presented with a bronze statue of himself. The marquees in the nearby town of Millinocket, Maine, welcomed him. He was the star of the Christmas parade and received a key to the city. While reporters took notes and tape-recorded his comments, book publishers were trying to sign him to contracts. Hollywood agents bargained for the right to film his story. Not a day in the life of your average long-distance hiker. For starters, this 50- year-old recovering alcoholic is blind and is the first sightless person to complete the AT. He never saw’ the trail in front of him, or the white blazes that mark the way, or the boulders he scrambled over, or the cliffs at his side, or the rivers he crossed, or the snakes or bears. His guide-dog Orient saw it all, though, and helped Irwin achieve what few sighted people manage to accomplish. ‘While most hikers carry a printed trail guide, Irwin’s data was on cassette tape—locations of shelters and springs, routes into towns to resupply, mileage in between. Members of his church in Burlington, North Carolina: Mailed supplies to post offices along the way. Orient led the way by following the scents of previous hikers. Long-distance hikers don’t get many opportunties to shower, so the scents were strong. “I got lost more with other hikers than when Orient and I were alone,” Irwin says. “People would get to talking, keep their heads down, and miss a turn blaze. Orient learned to look for and read blazes.

“Orient watched my right foot with his right eye. If there was something on the trail that I’d fall over, he’d take a step and wait for me. The speed with which he did it let me know how safe it was— whether I could plow through or had to test each step before putting my full weight down.” In the early days in Georgia, Irwin would carefully test the ground and lock his ankles before putting his weight down. He didn’t make good time, however, so he started just plodding along. “My ankles twisted so many times the ligaments are all stretched out. It only hurts for a minute or two.”

Seeing-eye dogs are trained to guide their owners through city streets and to alert them of a step two inches and higher. Orient learned by trial and error what heights he could get away with and what Irwin couldn’t tolerate. “When a tree was down across the trail, my head would always clear by about six inches.” When Orient would stop, it signaled a problem, and Irwin would swing his ski-pole hiking staff around the area until he found the obstacle.

I watched the pair rock-hop across a stream when we hiked together in Pennsylvania. Remarkably, Irwin placed his size-14 feet squarely on the stepping stones. He would sense the movement of Orient’s body through the harness and leash. When Orient would take a big step, Irwin knew that he also had to take a big step.

Despite his uncanny abilities, Irwin had his share of spills on the trail. In Georgia he fell some 40 times a day. He wore knee pads, always had scrapes healing on his legs, broke a rib once, and smashed a finger. When he fell, he says he would be grateful he wasn’t hurt. ‘When he did injure himself, he would tell himself to be grateful he wasn’t hurt worse. He soon learned what all long-distance hikers know: Success depends on your mental toughness and the ability to withstand the hardships of the trail. A good attitude and burning passion mean more than strong muscles. “Acceptance is they key to my world. Accept the sun, accept the rain, accept the cold, accept the Appalachian Trail.”

A sense of humor helps too. He tells of the time he received a care package and wolfed down some beef jerky. It wasn’t until he later thanked the sender for the tasty treat that he learned they were doggie chews for Orient.

Of all the trials and tribulations encountered, physical and mental exhaustion proved to be the major problems. Any AT hiker can attest to the physical rigors: Walking an average of 15 miles a day, up and down mountain with 50 or 60 pounds on your back. But when you’re blind, intense concentration comes into play. Irwin had to use rock-climbing techniques on ascents, feeling for depressions in the rock while keep- ing his body low and close. Orient couldn’t climb, so Irwin had to lift him over his head. Once, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, they came to a 25-foot drop over a rock slab. Saplings that might have been used as hand holds had been pulled up, so Irwin had to wedge his hand into a crack while holding Orient in his other hand. It was a precarious route, with him teetering most of the time, bearing the weight of a full pack, trying to push Orient up.

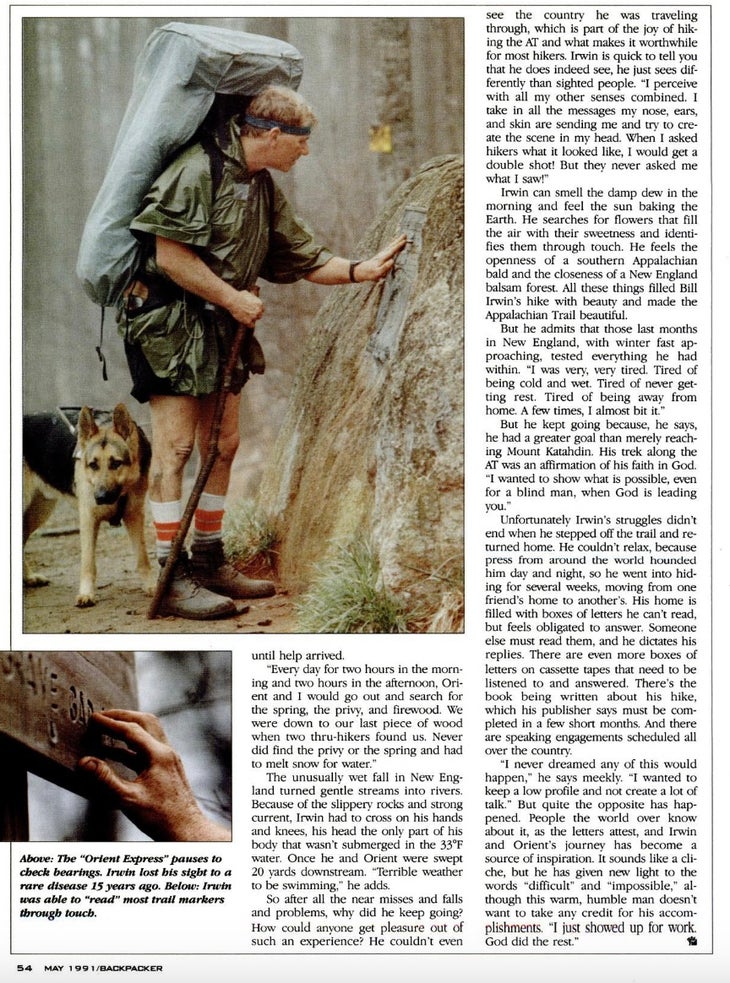

Vermont’s slippery, narrow log bridges landed them in oozing mud more than once. Because Irwin took so long to complete his hike (eight months), he was out longer than most thru-hikers, and the weather turned nasty and cold. He contended with temperatures in the teens, 100-mph gusting winds on open, exposed summits, and a blizzard that dumped 28 inches of snow. After the snow reached eight inches, Orient could no longer find the trail, 5o they stayed in a ranger’s cabin on a Maine mountaintop. They waited four days until help arrived.

“Every day for two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon, Orient and I would go out and search for the spring, the privy, and firewood. We were down to our last piece of wood when two thru-hikers found us. Never did find the privy or the spring and had to melt snow for water.”

The unusually wet fall in New England turned gentle streams into rivers. Because of the slippery rocks and strong current, Irwin had to cross on his hands and knees, his head the only part of his body that wasn’t submerged in the 33°F water. Once he and Orient were swept 20 yards downstream. “Terrible weather to be swimming,” he adds.

So after all the near misses and falls and problems, why did he keep going? How could anyone get pleasure out of such an experience? He couldn’t even see the country he was traveling through, which is part of the joy of hiking the AT and what makes it worthwhile for most hikers. Irwin is quick to tell you that he does indeed see, he just sees differently than sighted people. “I perceive with all my other senses combined. I take in all the messages my nose, ears, and skin are sending me and try to create the scene in my head. When I asked hikers what it looked like, I would get a double shot! But they never asked me what I saw!”

Irwin can smell the damp dew in the morning and feel the sun baking the Earth. He searches for flowers that fill the air with their sweetness and identifies them through touch. He feels the openness of a southern Appalachian bald and the closeness of a New England balsam forest. All these things filled Bill Irwin’s hike with beauty and made the Appalachian Trail beautiful.

But he admits that those last months in New England, with winter fast approaching, tested everything he had within. “I was very, very tired. Tired of being cold and wet. Tired of never getting rest. Tired of being away from home. A few times, I almost bit it.”

But he kept going because, he says, he had a greater goal than merely reaching Mount Katahdin. His trek along the AT was an affirmation of his faith in God. “I wanted to show what is possible, even for a blind man, when God is leading you.”

Unfortunately Irwin’s struggles didn’t end when he stepped off the trail and returned home. He couldn’t relax, because press from around the world hounded him day and night, so he went into hid- ing for several weeks, moving from one friend’s home to another’s. His home is filled with boxes of letters he can’t read, but feels obligated to answer. Someone else must read them, and he dictates his replies. There are even more boxes of letters on cassette tapes that need to be listened to and answered. There’s the book being written about his hike, which his publisher says must be completed in a few short months. And there are speaking engagements scheduled all over the country.

“I never dreamed any of this would happen,” he says meekly. “I wanted to keep a low profile and not create a lot of talk.” But quite the opposite has happened. People the world over know about it, as the letters attest, and Irwin and Orient’s journey has become a source of inspiration. It sounds like a cliche, but he has given new light to the words “difficult” and “impossible,” although this warm, humble man doesn’t want to take any credit for his accomplishments. “I just showed up for work. God did the rest.”

From 2025