No Way Out: A Hiker’s Journey Into The Maze

No Way Out: A Hiker’s Journey Into The Maze

The Maze District of Canyonlands National Park is around 30-square miles of rugged, remote red-rock canyon, twisted into a nearly impenetrable labyrinth. Writer David Sumner dives in feet-first in this 1982 story from the Backpacker archives.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Sweet spring, “when the world is mud luscious and puddle wonderful,” wrote the poet e.e. cummings. But spring in the Colorado mountains is not sweet and there is too much mud. It is this way where I live, in Crested Butte. For a week or more in April or May most locals leave, generally heading south. The upscale go far south, or at least far: to places like New Zealand, Belize or Greece. Lesser folk tend southwest to more obscure destinations: Grand Gulch, Dark Canyon, Owl Canyon, Emie’s Country, The Fins— or The Maze.

So it is, on April Fool’s Day I leave for The Maze. This year in Crested Butte there is little snow to escape. It has been a rare, poor winter, but there is mud galore and the bad taste of faithless weather, of a relatively snowless winter untrue to its name. In a ski town, that strings you out, sets you on edge. You can’t ski right, can’t make much money, can’t let go. By April Fool’s, I just want to escape.

Heading west through Grand Junction I pick up Roy Leedy, a gaunt, thoughtful fellow. When Roy works, it’s as an auto mechanic or customizing old VW buses: on the side he plays the silver market and soothes his soul by vandalizing sexist billboards. Roy ponders lot and when he talks, it’s in bursts, a kind of mutter-with-twang. A detour south to Moab, Utah, completes our party. Peggy Kuhn is another kind of spirt, cheerful and upbeat. Without her Roy and I might never reach The Maze or anywhere else. We’d just go our Ways—not very far—choose our spots, and sit for week. But not Peggy. With her we move, march, go somewhere, wonder, exult. Peggy, also from Crested Butte, has been in the desert a week already, doing staff training with the Outward Bounders for whom she works. She is full of questions, information, stories, maps, energy and awe. Roy and I stand around the OB base camp, stunned by the bustle. “Let’s go,” Peggy almost sings. Sometimes it is hard to see her as human, and I probably don’t. Talk about sexism.

We chatter and drive, unwinding like sprung coils. Bye bye, mud season, bye bye. Long drives like ours are grace periods, chances to shift gears, get ready. Two jackrabbits exchange sides of the road. And somewhere off to the east, out in the space like a hole, is The Maze. We can’t see it. We drive toward it, and it draws us in. ‘A dirt road off Utah 24. White-faced cows, yucca, more dust and dark. We pull off and toss out our bags for the night. And just before sleep, a line from a poem for the stars: “like luminous bullet holes piercing the sky.”

THE LONG WALK

In the morning we hit the ranger station. The rangers know they are horribly out of place out here in the empty, empty space, uniformed according to regulations, with a TV antenna and trailers. Two men — orderly, punctual, polite — apologetic because they must ask you to register for the continuation of your journey. “Good luck,” we are told, and “The trailhead is off the rough road to the left. You’ll see it.” And we do. We park the car under a scrawny piñon, and we commence to assemble our gear. We’ve arrived. Arrived where? Where is this thing called The Maze? What is it?

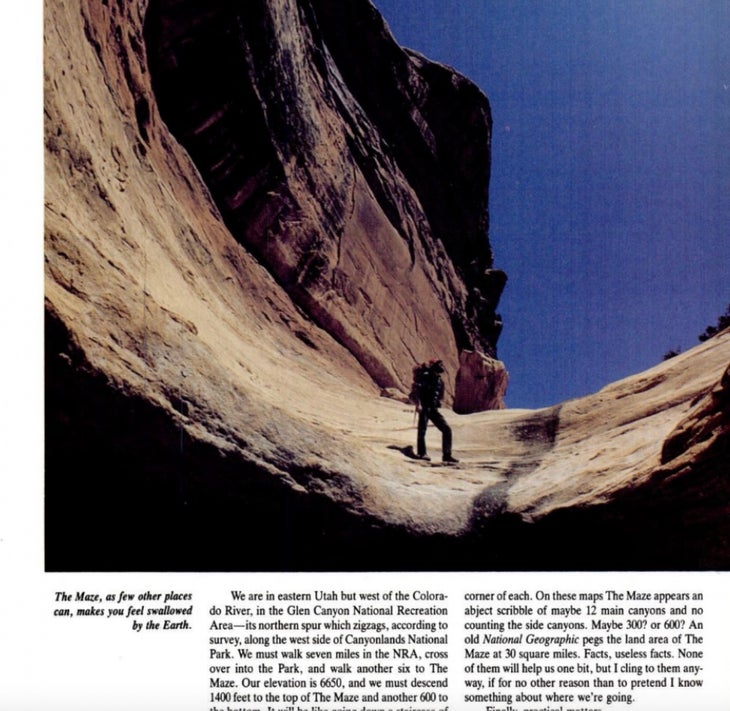

We are in eastern Utah but west of the Colorado River, in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area—its northern spur which zigzags, according to survey, along the west side of Canyonlands National Park. We must walk seven miles in the NRA, cross over into the Park, and walk another six to The Maze. Our elevation is 650, and we must descend 1400 feet to the top of The Maze and another 600 to the bottom. It will be like going down a staircase of two massive steps, one at the beginning of our trip, one at the end. In between is an enormous flat.

As for The Maze, I’d tried to find out what I could in books; which wasn’t much. Edward Abbey has a chapter on the place in Desert Solitaire: “deep narrow canyons down in there branching out in all directions . . . a labyrinth with the roof removed.” ‘The Maze also pops up here and there in Fran Bames’s Canyon Country Geology, mostly in connection with Cedar Mesa sandstone which i its dominant rock (whose colors remind Abbey of Neapolitan ice cream). “The Maze requires four USGS maps (15-minute series), because a part of the place has ended up in a comer of each. On these maps The Maze appears an abject scribble of maybe 12 main canyons and no counting the side canyons. Maybe 300 or 600? An old National Geographic pegs the land area of The Maze at 30 square miles. Facts, useless facts. None of them will help us one bit, but I cling to them any- way,if for no other reason than to pretend I know something about where we’re going. Finally, practical matters. ‘Water? There should be plenty. In the canyon country April is the kindest month Rope? Bring a good one, 150 feet. You may need it. An extra day’s food? Good idea. In The Maze things don’t always go according to plan. A plan? Forget it So we set off down the North Canyon Trail, all switchbacks, and into Elaterite Basin. Our first stop: Big Water Spring. A strong wilderness trip can open odd doors in the mind.

And so as we trudge down those switchbacks beneath tall cliffs of bright rock, as Roy stops to peer under a drooping overhang of another, dirtier rock (“nice in here”). My old friend Joseph Conrad comes to mind. In particular I think of his Heart of Darkness and its suggestion that any extreme journey has the potential to take you to madness. That seems to be what I stumbled into on one or two wilderness trips of my own. Once, a decade ago, on a long archery hunt, I’d come upon a family of blue grouse—a hen and four poults —in a little subalpine meadow. Blue grouse are known as “fool hens” because their impulse is confusion rather than flight. My five birds ran around like distracted drunks, peeping and cheep- ing, and one by one I skewered them with arrows in the name of camp meat. The hen first and then the poults; Mommy and then the kids ‘When an arrow missed and stuck in the ground, I dash over, grab it and gleefully shoot again. The last poult was still running about, going cheep-cheep, all by itself when, incredibly, I beheaded it with a shot high in the neck. I felt giddy and drunk.

I’ve thought of that episode from time to time since, and I have wondered about the relationship between wilderness and savagery and madness. Now once again I shuffle through these thoughts as we pick our way toward the base of North Canyon. I’m a little afraid of unraveling somewhere out ahead of us. Perhaps the long winter back in Crested Butte has been more wearing than I knew. So I mark our progress—down in elevation, back in time, out into space. Back in time. The orange cliffs of North Canyon are Wingate sandstone — late Triassic, 195 million years old. This youngest and uppermost rock of our trip is formed of dunes piled up when thi region was a Sahara. Before that it was a wetter place of meandering streams and low lakes, and before that, in sequence, a shallow sea, a coastal beach, a tidal flat and an ocean bar, source of the oldest and lowest rock we will see, the Cedar Mesa sandstone down in ‘The Maze — Permian, 275 million years old, Abbey’s Neapolitan ice cream. More of those useless, reassuring facts.

We have dropped 1200 feet, mostly in silence. Yesterday’s exuberance is gone. Peggy hikes with her hands clasped as if in prayer. The long, level walk begins with the Orange Cliffs receding behind us and to either side — deeper into Elaterite Basin. “An empty immensity of earth and sky,” Conrad might have called it. Gray clouds drape futile banners of rain that simply evaporate before they reach the ground. Gray and grayer. The lowering sky clamps down on the basin like a lid. This place is an overgrazed zone of death, a stupefying void in which nothing moves. No rabbits, not even a vulture circling overhead. Ratty brush grows in spare disjunct clumps among shattered slabs. Six miles out we come to Big Water Canyon, which is no canyon at all, just a shallow wash. There is sheltering piñon, and cowpies. Big Water Spring is supposed to be around here, which is good because our water is low. Not much left of us, ether We pitch Peggy’s tent and crawl in to avoid the chill.

TO THE RIM

The snow here is feeble, and Big Water Spring pathetic—a greasy, slimy quagmire. Because we know we’ve another seven miles to The Maze, we rouse ourselves only enough to function, and again we walk. In seven miles there are three notable moments. First the sign, “Entering Canyonlands National Park, ” staked out there in the space, accompanied by a register on which previous travelers have written much snide commentary on the spring. No matter; it is a pleasure to arrive in an American national park by foot. The second moment is the first patch of exposed White Rim sandstone, eroded into a mosaic of depressions each less than an inch deep and holding fresh water. We drink but cannot fill our bottles. Finally we skirt the first canyon of The Maze, a colorful, distant reach eroded into the basin like a gash. With that, the gloom begins to lft, and I can feel my stride pick up. This has long since become a solitary trip, and Peggy and Roy are far behind.

I sense The Maze is near, can almost feel that hole out there and its pull, very close now, very close. The grade tops out. I leave my pack by a squat rock and walk slowly down to the overlook, the edge. This one I do not want to hurry. Now I have reached my moment with The Maze. It is bright, very bright. Seeing The Maze for the first time is like having a grenade go off in my head. The whole mechanism of comprehension bursts apart. I am looking through a wide gap, and a hawk wheels through the space, so close I could hit it with a stone. The panorama is entirely of canyons with walls like drooping tiers, rounded and bulging. The rock seems to have a characteristic curve which repeats itself, but not enough to become orderly.

Piñons and juniper, small puffs of green, grow on some ledges. Meanders lead to dead ends. There is no seeing the bottom, the canyon floors. But scattered atop the snaking rims that divide one cut from the next (in bizarre contrast with the swirl below) are stark, geometric formations ke fingers and books, pointing up and standing on end. In the near distance four huge maroon books stand in a row. Peggy and Roy arrive, move to the edge. For maybe an hour we stay apart. Gradually, from the spot where we arrived, each of us moves farther along the rim, assimilating a little more, a little at a time. More canyons only. The Maze will not assemble. Like the folds of a vast human brain, it seems infinite. Finally we regroup and descend.

DOWN IN

Look at the whole Maze, and there’s no way to cope. Its like staring into the face of fire. But take the place a little at a time, and it becomes comprehensible, even engaging. We find the trail, which begins with an eight-foot drop over the White Rim, then chutes beneath a line of columnar pedestals capped by thick slabs. Walk along a red ledge. Squeeze through a sot. Amble out a rim. Inch overa bulge with hands and feet in tiny depressions (old steps?).

Without cairns this descent would be a bewildering maze in itself. With them it in a geological funhouse that ceases to be fun only when your pack gets stuck in a slot or when excess exposure is involved. We don’t need the rope. And then we are ‘down’. The canyon floor is mostly sand, and we find water quickly. Sometime recently this canyon has flash flooded; brush and reeds are wrapped around cottonwoods four feet up the trunk. (Juniper is the other significant tree here. Juniperus monosperma: Utah single-seed juniper.) On a high, sandy bench we make camp, once again almost by dark. Beginning next morning we have four days in The Maze. We have arrived, and the question is what to do. Here is what happens.

Day 1: What is The Maze like? We stay within a mile of camp and figure out how the place works. | explore two small branch canyons and Roy a third, a main stem. Independently we both study ledge systems and how to get from one up to the next, up to the next. Peggy goes her way along canyon floors.

Day 2: Can we get out? The three of us find another way out of the Maze (for there must be other ‘ways out), arriving at the four huge geometric formations like books standing on end. They must be 100 feet high. From there Peggy and Roy make an overland, rock-hopping jaunt south to the Land of Standing Rocks (those fingers pointing straight up). I stay near the books and hunt for unnamed arches.

Day 3: How far can we go? I wander up a long, sinuous canyon. Roy and Peggy pull out the rope and climb. They find four arches, one above the other, formed in overhanging rims like what? Well, kind of like giant toilet seats. Then we leave. This is not a close trip. Some I’ve taken become intense, traveling dialogues. Here each of us seems to be drifting in comfortable proximity with the others, but still essentially alone. The spring days are warm and sunny, and I find myself reacting to this extraordinary place in three ways.

‘The first and simplest I call being there. I have nowhere I must go, nothing I must do. I can putter about vacantly, or sit. Mostly I just let my eyes roam over color and form—especially form, the design of rock. The rock is tan and buff, maroon and pink, bright in the sun, pastel in the shade. Its forms are like cloudscapes or the swirl of surf. On a low wall I find a rhinoceros, on a small flat a perfect toadstool with a ruddy cap and light stem, on the rim above our tent a Barbary sheep. There are castles and spires and domes and a scary little arch like a howling mouth.

The second way is as a strictly amateur ecologist. To enjoy seeing how things work, and fit, and ‘adapt. In The Maze life spreads thin and gropes for both water and light. Clumps of grass scatter on ‘small dunes; the cottonwoods are stunted, excessively branched. How, I wonder looking down from a rim, was The Maze formed? How could such a small drainage area, in a land of so little rain, create such a large, many-branched network of canyons? ‘The mind runs. Branching canyons and branch- ing trees: what of that? Like no other wild place I’ve been in, The Maze teases my curiosity. What of the branching veins in my hands, of the branched lightning we saw back in Elaterite Basin? ‘Curious thoughts in a strange place.

My third frame of mind is more inward. The Maze has somehow kicked loose disjointed old ‘memories from my academic days, not only of Conrad but of other writers I once read or taught. Down in, The Maze has no hint of the savage, tangled gloom of the Congo in “Heart of Darkness.” This is another kind of wilderness, seeming excessively bright— bright as in both “light” and “intelligence.” If from the rim The Maze seemed a giant brain, then down in I have the comfort of being in a rational place that asks to be explored. And maybe solved. And maybe not. It is the sense of maze itself that appeals. Of the canyons two kinds of rock, the buff is usually firmer and rounder, the maroon friable and ledgy. As you clamber up, either can stop you like a wall: the buff with a smooth, impossible bulge, the maroon with an overhang beyond your reach.

So you backtrack, work 20 yards o the left and try again. And perhaps make it up two more levels before another dead end. Over and over you do it, often perplexed but never overwhelmed. Finally you decide you’ve had enough of this little canyon, enough of this little box in the rock, and so back down you go to its sandy floor. Off you amble to the next canyon. And then the next. And the next.

I suppose I could feel like a rat in a Skinner box, testing corridors in search of food, first in frustration and then in growing panic as the dead ends mount. But I am not desperate for a way out to a reward. And I wonder if a maze must have a way out—or is that just our demand? Cheerfully I wander from canyon to canyon, imagining I can find and experience anything I wish. Here in The Maze I think I can go on forever. But instead I tire, fashion a bed in the sand, and nap. When the afternoon shadows come, and the chill, I waken and return to camp.

Finally our last day in The Maze. I decide to walk up a long canyon, South Fork it is marked on the map, though the south fork of what i unclear. I take lunch and a full water bottle. And set out. Every journey has culminating point, that moment when you have traveled furthest, and it may or may not have anything to do with time or physical distance. It is usually very simple, and clear. For a long time you know you are going out, and then something happens. It can be anything: reaching a summit, almost drowning, spearing blue grouse, whatever. From that point on you know you’re on the way back. I haven’t reached that point as I head up the South Fork, but I know it is out there.

The map shows the canyon 10 be seven or eight miles long (with all the bends, this is a guess), and I know I will not reach the end. So I will just go. The day is warm and clear, like high summer back in Crested Butte. For a while I just walk and look, entirely outside myself. I follow a bend to the left, then to the right, then back to the left. The side canyons up here are modest, and I stay with the main stem, just walking. Sometimes I watch my feet as I did crossing Elaterite Basin. No other footprints here, not even a deer’s. I would like to see a deer. The rangers said they are here. (How do they get in, and out?) But even the birds, so noisy early in the day, are quiet.

The South Fork is a sun-stunned silence. Only the sound of my breathing and my feet in the sand. Finally I round a bend to the left and decide to climb a sandy slope up to a wall. I walk along the wall, move out onto a point of rock and sit. Nothing, notevena light wind. Just the sun and the rock. And then I know I have gone as far as I will go this time.

BACK OUT

Roy and Peggy are at camp packing the tent when I arrive. Aside from sociable greetings and brief reports of our day’s doings, we’ve lttle to say. ‘We follow the cairns up out of The Maze, reach the im just at dark, walk for a long time by starlight into asteady wind, then toss our bags into a shallow wash and sleep. The next day is the mindless walk back across Elaterite Basin. Then the grind up North Canyon, my car under the piion still, and a night drive in rain to Roy’s trailer in Grand Junction. Another half-day and I am home in Crested Butte.

I have thought little about The Maze since then. It isn’t the kind of place, or experience, you think about. All of a sudden, though, it will just well up and be there. And I feel an eerie resonance. One by ‘one images come to mind: a curve of rock, a cottonwood branch, the sand, the colors, the light. Unlike other places I’ve visited, I feel no burn- ing desire to return to The Maze. But one day that urge will come, and when it does I will be helplessly without choice, and I will go back down in, for a very long time.

From 2025